Did you know that there are plans afoot to reform copyright law here in South Africa? A new draft policy on intellectual property was proposed at the end of last year. Broadly speaking, it was welcomed by healthcare activists, who campaign to allow drug companies to produce cheap generic medicines, but not so much by people in the creative industries who saw it as threatening their rights.

In developing markets for technology and IP people look to countries like the United States and they see companies there arguing for ‘maximalist’ IP and locking down more things with stronger fines for people who break the rules. They argue for more expansive patent systems and everything to be copyrighted. They see that, and they see pressure groups like the MPAA coming out to speak to people and going “you should have an IP industry like us”. The truth is exactly the opposite. Maximalist IP is really good if you’re in a competitive battle with emerging creative industries. The best thing you can do is lock down IP, so you get all the income coming from your properties and other people have to compete with very established and profitable IP industries.

In countries like Chile and across Latin America there’s a growing realisation that this is an unbalanced playing field. They are looking more to the early years of the US’ history, when the country was infamous as a pirate state. It was the Pirate Bay of its time. In an attempt to establish it’s own industries, it had very liberal copyright laws and didn’t agree with the stronger laws that were in place over in Europe. It did things like move its entire film industry to Hollywood and the West Coast to evade copyright restrictions that were going on in the East Coast. The history of growing creative industries has always been about liberal copyright so people could compete and learn and use each others’ ideas without having to go through endless licence preparation for those kinds of things. Part of the international world of copyright has been a gradual shift in the attitude from the Global South from feeling that what they really needed to do to compete against the West was to really lock down their IP – and you see this still in issues like indigenous intellectual property – to this realisation that actually, the best thing for a young IP system is a very permissive copyright regime.

This is not about throwing away copyright entirely, it’s about thinking ‘where do we go next’ and how do we make it work in an internet environment.

The Korean economist Ha-Joon Chang talks says that if hadn’t been for the fact that he was learning from photocopied textbooks in the 1960s and 70s, he wouldn’t be one of the most respected teachers at Cambridge University today.

Absolutely. If you look at a situation where you can enforce – both legally and technologically – access to content, that’s always going to have a negative effect on countries and communities who can’t get access to that data. It’s the classic example of going to a YouTube video and getting the message which says “I’m sorry you can’t watch this video because it’s not licensed for your country”.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that people in that country shouldn’t see that video, it just means no-one has sat down and gone through all the paperwork to include you in some agreement. That’s going to penalise countries where these big IP companies don’t see any profit. Contrast this with, say, the software industry, where the software industry has always had a very complicated relationship with things like digital rights management (DRM). In the old days, Microsoft had to make a decision about whether or not to put technology into Microsoft Windows and prevent people from copying it. And it was better for them to have people using copies of Microsoft Word that were five generations down from a new one in countries like China and other developing nations, because in that situation when it comes to actually buying a copy you’re not going to do anything than buy Word because that’s what you know and everyone else uses.

So in terms of deciding what the policy of a country is regarding the future of copyright, there’s a really strong mapping to the ideas of the medical field. What you want is a liberal copyright regime that understands that in some cases, what you want is to have an easy and quicker path to generics and so forth. In the modern, technological creative industries what you realise is that you don’t want things like software patents.

Software patents are something that really only exist in the US and that the US is trying to export overseas, but they’ve had a really bad effect there. There’s a massive movement there now, supported by these companies that are in these terrible wars to the death – like Samsung and Apple – who are trying to reform this at the same time as we’re going out to other countries and saying “no, you should totally do software patents”.

[symple_box style=”boxinfo”]

This is not about throwing away copyright entirely, it’s about thinking ‘where do we go next’ and how do we make it work in an internet environment.

[/symple_box]

Then they lock it all down in global treaties that effectively prevent anyone from innovating in copyright. So a really good example is that in the US, there’s now an open question about whether or not it’s illegal or not to lock a mobile phone. Which is such a dumb question for the rest of the world. It’s ridiculous that it would be somehow illegal.

The reason it’s illegal in the US is a side effect of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) laws which criminalises breaking DRM and digital locks. By accident of the law, it also includes unlocking mobile phones. One of the problems is that people sit down and decide “OK, let’s pass a law that makes it legal for people to unlock phones in the United States”. And then they discover – or at least they claim – that because of attempts to export the DMCA the US has actually signed treaties that are irrevocable with other countries that agree the principles of the DMCA. Which means that now, not only can the US not change that law because it’s government by treaty but now South Korea discovers that it can’t make unlocking phones legal.

So there’s this terrible nest of international copyright law and people have to really think about whether or not they want to buy in to this world where everything that everything which is not legally permitted is forbidden. That’s the copyright maximalist’s position. Technically, under laws like that, forwarding on a friend’s email without their permission is illegal, because their email is copyrighted thanks to other crazy treaties that were signed in the 1970s. And given that the internet is just this massive free copying machine – and I don’t mean that in a ‘piracy’ kind of way, it’s just how the internet works, copying stuff from a server to your machine and a web browser – given that, to try and make sure every act of copying is locked down and legal and has to be check by a lawyer means that you just gum up the entirety of the net.

[symple_box style=”boxnotice”]

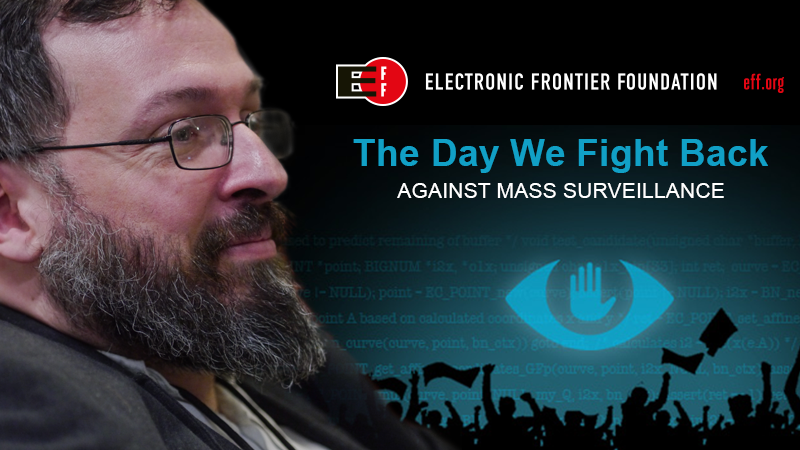

Click here for page 3 – “We at the EFF… see the internet as an ultimately liberating force”

[/symple_box]