I remember in the UK there was an outcry when we discovered almost anyone in an ‘official’ position – including local council clerks – could use the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) to access phone records…

In Nairobi, a friend of mine was talking to a police chief there who says that over half of petty crimes that they deal with now they use mobile phone records to solve. And you can totally see why. You have a robbery or something that’s going on, so you go through the phone records of the usual suspects and you find out that they were in the same area, so you go and have a word. This stuff is incredibly useful for finding out what everybody does in the society that you live in. That’s why the NSA wants this data as well as the local police chiefs.

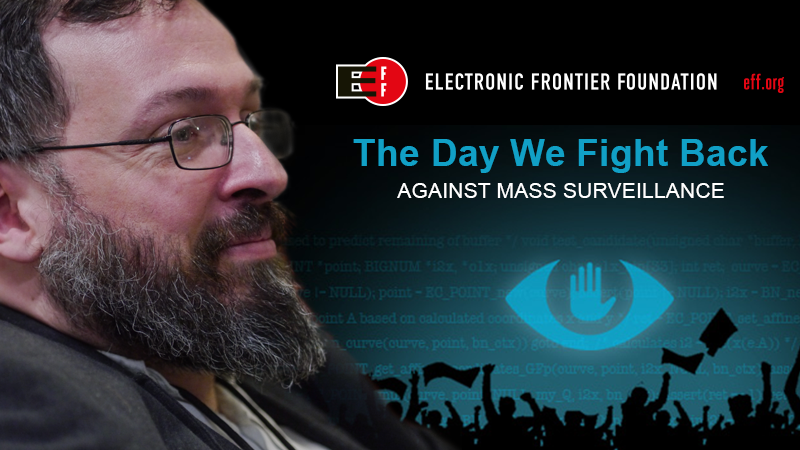

One of the challenges we’re facing is that it’s hard enough educating journalists and people who have grown up with the internet about issues like copyright and online privacy and PGP. How do you go about trying to explain the NSA to someone who’s just got their first cellphone? How do you get the message out?

Some of it is just time. When people use technology they develop intuitions about how stuff works and some of them are correct, and some are wrong. But we develop an instinctive understanding of at least part of what’s going on, and the more you tell stories about when things go terribly wrong and the more you explain things, the more it percolates through.

There are a lot of issues that 15 years ago, when we were talking about them, people didn’t understand because they weren’t part of their daily life. We were arguing about this thing called Digital Rights Management and people would just go “what?” and we’d say “it’s very bad!”. To this day, it’s hard to say why it’s very bad, but trust me, it is. Then there was this incident where Sony tried to copy protect a bunch of CDs by putting in evil software that took over your entire computer. The Sony Rootkit. It was this huge scandal, but the reason why people really understood what was going on is because they were used to ripping CDs on to their iPods (at that point) and they understood someone was taking that right from them. And that was a sea change in that debate.

Do you think the public understood the technical nuances between a rootkit and DRM?

No, and I don’t think you have to in order to get a sense of violation at what’s going on. It’s the same with the NSA stuff, there’s also this talk about people not really caring about this sort of stuff. But they’re interested in reading about it, and every time they read about it they think a little bit more about the consequences. And you look at your mobile phone and you start thinking about it in a very different light.

One of the things we did at this conference was we got them to take out their phone and give it to the person next to them. Suddenly you have a really emotional reaction about what they have in their hand. And the moment they do that they start thinking about the data they’re storing on their phone and how they win the fight. And in that sense, we’re on the right side of history here. The more people use this technology the more they will realise how it can be abused by those in power and the more they will realise how much they want to protect the abilities they have.

In your work with African journalists, have you come up against the attitude that people are generally very scared of crime, and will allow all sorts of privacy violations in the name of staying safe.

It was funny. We were talking about all this encryption and extra-long passwords and all the things we do to prevent against online attacks, and a young journalist here put her hand up and said “maybe one of the ways you can explain this to people here is to talk about how many alarms they have and how they take so many steps to protect [their physical belongings]”. I’ve never heard someone actually argue that level of protection as a positive metaphor in that area.

But the fact is that people use crime like they use terrorism in the US, as an excuse to push through greater surveillance powers.

A great example is in Nigeria, where the country suffers this terrible reputation as being ground zero for international scam artists. As a consequence, the government really wants to present a strong international appearance of doing something about cyber security. That’s always a risky situation, because suddenly you end up building this repressive apparatus in your own country for international reasons and chilling legitimate use of technology in your own area which means that people end up doing those sorts of scams anyway because there’s no other alternative.

If we turn the internet into this huge spying apparatus, that will be useful in the short-term for law enforcement. But at the same time it creates a society that we have to live with for the next 100 years. And we’ve spent the last 100 years or so learning that actually, you don’t want 100% perfect law enforcement because then you end up with a fascist state. Great, the trains run on time but anyone who voices objections gets thrown in jail.

Until we understand that there are limits we want to place on government and law enforcement for our own good. The challenge we have right now is to establish what those limits should be for a modern police in a modern world – before we find we’ve given our governments and police powers that we will never be able to take away from them.

There’s a big debate going on about e-Tolls here in Johannesburg, and there’s a lot of protest against them, but the privacy issue hasn’t really come in to it much. There was a moment when one of the officials said “don’t think about vandalising the e-Toll gantries, because if you’re on the highways we’re watching you.”

The thing about politicians is that we know they’re watching common people, but they’re also watching other politicians too. Even within parties there are different groups. I’m really serious about this. If you build a surveillance structure using mobile phones, which is really easy to do, then whoever controls that controls the state.

How do you stop that? You’re not Richard Stallman, you don’t refuse to carry around a mobile phone. There is that acknowledgement that these technologies are, on the whole, good. So what’s the happy medium in terms of using them?

This our big dilemma. When you think back to the days when we only had computers and laptops, people had options. Not every body chose those options. But you can put pressure on each of those parts to secure things don’t. But even as someone who works in the world of high-tech, who is based in Silicon Valley and really cares about civil liberties and human rights, with some of the best minds in technology… we’re absolutely racking our minds to head off this Orwellian world where everybody is tracked – and we don’t have great solutions.

Steve Song, who works for Village Telco and does a lot of work in South Africa, has this idea for mesh communications systems that are a bit like a ‘grow your own’ phone company. That has some ramifications which are very good for privacy. So if something like that takes root we’re looking at a better world in terms of controlling your own data.

[symple_box style=”boxinfo”]

“Politicians are watching common people, but they’re also watching other politicians too…”

[/symple_box]

The bad side of that is that if the local mobile phone company sees that as a threat to its profits it will do a great deal of work to prohibit this kind of thing. But as to the question of how can we build a mobile phone system that’s actually protective of human rights and civil liberties, one of the things we can do is to seize back control of the devices we do own.

Right now we have limited menus of what we can run on our phones, decided by the App Store or Google Play. What’s on your phone is decided by you, Apple and your local phone company, and you are last on the list of who gets to choose stuff. It doesn’t have to be that way. It’s possible to build phones that are protective of your privacy and don’t have that kind of sharing and control with third parties.

To give some examples, there’s a group called Cyanogenmod, who give you software that can overwrite existing software on your Android phone. They give you software that automatically encrypts your text messages – which is amazing, it used to be that SMS messages were vulnerable to your phone company or government intercepting them, but practically anybody else in that whole chain. Now they’re really, strongly protected. Similarly you have some guarantee that the software agencies like the NSA want to install on them is missing.

The biggest problem with mobile phones, however, is that they are like Jekyll and Hyde. They have not one computer but two computers in them. One is the thing that runs iOS or Android on your screen, the other is the baseband transmitter. And we have some reasonably strong evidence to suggest that this has deliberate backdoor in it to turn your phone into a long distance remote bug. It might be able to turn on the microphone and record anything you say near it.

The biggest problem is this issue of phones as tracking devices. That’s going to require legislation or some really technology to circumscribe it.

Google balloons. That’ll do it.

Yeah! In all honesty, you’re so much better protected by using your phone as a WiFi device than you are using mobile infrastructure. So something like Google balloons or anything that gives a big WiFi network to everyone will improve that kind of security.